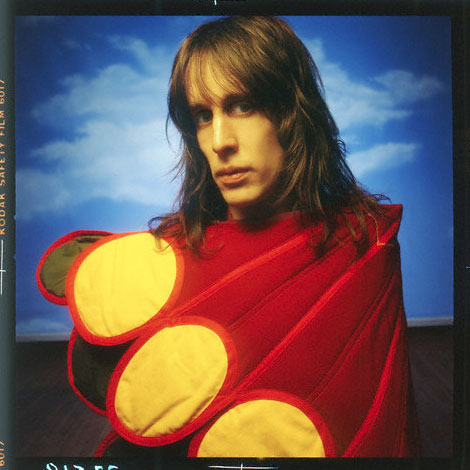

Todd Rundgren

Inducted: 1989

Todd Rundgren’s best-known songs – “I Saw the Light,” “Hello, It’s Me,” “Can We Still Be Friends,” and “Bang on the Drum All Day” – suggest that he is a talented pop craftsman, but nothing more than that. On one level, that perception is true since he is undoubtedly a gifted pop songwriter, but at his core Rundgren is a rock & roll maverick. Once he had a taste of success with his 1972 masterwork Something/Anything?, Rundgren chose to abandon stardom and, with it, conventional pop music. He began a course through uncharted musical territory, becoming a pioneer not only in electronic music and prog rock, but in music video, computer software and Internet music delivery. As his career wound into its third decade, Rundgren concentrated on behind-the-scenes innovations, but during the ’70s and ’80s he maintained a relentless work schedule. He released up to two albums a year either as a solo artist or with his band Utopia, while producing acclaimed, successful records for artists as diverse as Badfinger, Meat Loaf, Grand Funk Railroad, the New York Dolls, and XTC. Given such an extensive catalog, it’s not surprising that there’s a vast variety of styles within Rundgren’s music – which is either rewarding or frustrating, depending on the album. Also, more often than not, the singles from each record do not offer an accurate indication of what the remainder of the album sounds like. Such an approach severely curtailed his mass appeal, but it helped him cultivate a ferociously dedicated cult audience.

During the ’70s, his records were underground favorites, and his albums continued to chart until 1991, nearly 20 years after his commercial peak. In those 20 years, Rundgren may have existed largely on the fringes of pop music, but he produced a body of work that ranks as one of the most intriguing in rock & roll. A native of Upper Darby, PA – a suburb of Philadelphia – Rundgren learned how to play guitar as a child, teaching himself after his initial round of lessons ceased. As a teenager, he absorbed pop music from Motown to Liverpool and formed Money, his first band, when he was 16. Following his high school graduation, he moved to the resort town of Wildwood, NJ, where he regularly sat in with a number of bands. Eventually, he became a member of the blues group Woody’s Truck Stop, which soon became based in Philadelphia. Rundgren stayed with the band for several months, but when the group began to move toward hippie psychedelia, he and Carson Van Osten bailed to form the Nazz in 1967. Taking their name from an obscure Yardbirds’ song and inspired by a variety of British Invasion groups, from the omnipresent Beatles to the cult favorites the Move, the Nazz were arguably the first anglophiles in rock history. There had been many groups that drew inspiration from the Beatles and the Stones, but none had been so self-consciously reverent as the Nazz. Playing lead guitar and bass, respectively, Rundgren and Van Osten were joined by drummer Thom Mooney (formerly of the Munchkins) and lead vocalist/keyboardist Stewkey (born Robert Antoni). By September 1967, the group received some financial support from local record store Bartoff and Warfield, who also put them in touch with John Kurland, a record promoter who was looking for a guitar pop band. Kurland took a shine to the Nazz and signed on as their manager. Kurland and his associate, Michael Friedman, had the Nazz sign with SGC Records – an off-shoot of Atlantic Records and Columbia-Screen Gems – in the summer of 1968.

The group’s debut album, Nazz, appeared in October, supported by the single “Hello It’s Me.” Although the song would later become a major hit for Rundgren as a solo artist, the dirge-like original version barely scraped the national charts. Despite the lack of success, the record – particularly the Nazz’s self-production of “Open My Eyes” and “Hello It’s Me” – attracted some good notices. Taking these as a cue, the group began work on an ambitious, self-produced double-album, named Fungo Bat. By the time it was released in April 1969, it was trimmed to a single album, Nazz Nazz. In the process of editing, much of Rundgren’s newer, Laura Nyro-influenced material – which he had sung himself – was left on the shelves. Neither the management nor his bandmates gave Rundgren much encouragement to sing, nor was his new introspective direction warmly received by his colleagues. Faced with a no-win situation, Rundgren left the group not long after their summer 1969 tour. Stewkey took control of the Nazz, erased Rundgren’s vocals from the album sitting in the vaults, and replaced them with his own. The result was released as Nazz 3 in 1970, but it stiffed.

Rundgren, meanwhile, became an in-house producer and engineer for former Bob Dylan manager Albert Grossman’s fledgling studio and label, Bearsville Records. Around the same time, Rundgren formed a band called Runt. In reality, Runt was little more than a front for his burgeoning solo career. He played all of the instruments except drums and bass, which were usually handled by brothers Hunt and Tony Sales. Runt – either Runt’s first album or Rundgren’s first solo album, depending on your point of view – was released on Ampex Records in the fall of 1970. The album slowly earned an audience, with the single “We Gotta Get You a Woman” climbing into the Top 20 in early 1971. His modest success was enough to convince Grossman to sign Rundgren to a long-term contract with Bearsville. Apart from a re-release of Runt, the first Rundgren album to appear on Bearsville was Runt’s final record, The Ballad of Todd Rundgren, a record that was reminiscent of such melodic singer/songwriter peers as Carole King and Laura Nyro, yet it had a subtly bizarre sensibility and quirky sense of humor that gave it a distinctive character.

As he pursued his solo career, Rundgren quickly earned a reputation as a talented producer/engineer. His first production was for American Dream, but he quickly graduated to the big leagues thanks to his association with Grossman. In 1970, he engineered the Band’s Stage Fright and Jesse Winchester’s acclaimed eponymous debut. These two productions set the stage for Rundgren to take the production seat that George Harrison left vacant; the result was Badfinger’s Straight Up, which gave him a huge hit with “Baby Blue.”

It wasn’t long until Rundgren had a huge hit of his own. He abandoned the Runt concept before beginning his third album, deciding to record the entire record himself. The result was Something/Anything?, a double-album set that cemented Rundgren’s reputation as a near-genius producer and gifted songwriter. Apart from the fourth side, which was constructed as a tongue-in-cheek operetta about a bar band, he played every instrument, sang every part, and produced the entire album. Hailed in the rock press as some sort of masterpiece upon its early 1972 release, it also won Rundgren a wide audience. The King tribute “I Saw the Light” reached number 16, and while its follow-up (the terrific power pop classic “Couldn’t I Just Tell You”) stiffed, the third single, a superior re-recording of the Nazz’s semi-hit “Hello, It’s Me,” climbed all the way to number five. In all, Something/Anything? reached number 29 and went gold, spending nearly a full year on the charts.

Stardom was handed to him with Something/Anything?, but Rundgren rejected it. He would later state that he had mastered pop songcraft and had no interest to simply repeat himself through endless recyclings of “I Saw the Light” or “Hello It’s Me.” That’s certainly not what he delivered with A Wizard, a True Star, his 1973 follow-up to Something/Anything?. A weird sonic collage encompassing everything from psychedelia and Philly soul to Disney show tunes and vaudeville, the record may not have been an intentional move to shed his mainstream audience, but that was the ultimate effect.

As the legions of listeners who loved “Hello, It’s Me” departed, Rundgren’s cult following – the fans who did consider him “A Wizard, a True Star” – intensified. Rundgren played the role to the hilt, dyeing his hair in a rainbow of colors and turning in extravagant concert performances. His appearance may have flirted with glam or glitter, but his music was getting increasingly progressive. His next album, 1974’s Todd, may have had the occasional full-fledged pop song, such as the near-hit “A Dream Goes on Forever,” but it had more than its share of lengthy experimental instrumentals. This was the direction he decided to pursue and he decided he needed a full-fledged band to help him continue in the progressive direction. And so Utopia was born. Initially, the group consisted of three keyboardists (Moogy Klingman, Ralph Shuckett, and Roger “M. Frog” Powell), a bassist (John Siegler), a percussionist (Kevin Elliman), and a drummer (John “Willie” Wilcox). Balancing Utopia with his solo career, Rundgren became one of the most prolific artists of the decade. Released just months after Todd, Todd Rundgren’s Utopia consisted of only four tracks, all of which were mainly instrumental, none of which were less than ten minutes. Rundgren continued in that direction on his next solo album, Initiation, which was released in the spring of 1975. Its radio-play hit, “Real Man,” became one of his concert staples, but the true heart of the album lay in the half-hour-long synth experiment devoted to the second side. Mere months later, Utopia released Another Live, a wild live album devoted to long synth-driven instrumentals. Another Live proved to be the culmination of the synth experiments and, in some ways, the stretch of willfully difficult records Rundgren made during the mid-’70s. He kicked off the year with Faithful, an album that split into original pop material and re-creations of ’60s chestnuts from the Yardbirds, Bob Dylan, the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, and the Beach Boys. His resurrection of “Good Vibrations” brought him his first Top 40 hit in three years. That year, he also revamped Utopia, stripping away two of the keyboardists (Klingman and Shuckett), as Elliman and Siegler left. Kasim Sulton joined as the new bassist. Although the new Utopia’s first album, Ra, was a prog-rock album by any measure, it was less overtly experimental and heavier than before. Ra was released early in February 1977 and was followed seven months later by Oops, Wrong Planet, a record that found the quartet abandoning progressive music for streamlined pop-rock, with a mainstream hard rock bent.

By the time The Hermit of Mink Hollow was released in April 1978, it had been two years between Rundgren’s solo albums, yet it had been six years since he had delivered an album as unabashedly pop and accessible as Hermit. On the strength of the Top 30 success of the ballad “Can We Still Be Friends,” the record became a big hit, spending 26 weeks on the charts and peaking at number 36. He followed the record with the double-live album Back to the Bars, which was split between Utopia and solo material. As his solo career received a shot in the arm, his production career reached a pinnacle of commercial success with Meat Loaf’s Bat Out of Hell. The shamelessly bombastic record became an unexpected blockbuster, due in no small part to Rundgren’s cinematic production. Not only did it reap financial rewards, but it also opened the doors for a variety of production gigs; over the next year, he kept extraordinarily busy, working with everyone from old friend Patti Smith (Wave) to new wave pub-rocker Tom Robinson (TRB Two), as well as arena rock goofs the Tubes (Remote Control). Given that Rundgren had been releasing records at such a rapid rate throughout the ’70s, it comes as a shock to note that neither he nor Utopia released an album during 1979. That’s not to say he wasn’t busy. Not only did he have his production work, but during 1979, Rundgren opened Utopia Video Studios, a cutting-edge video production enterprise. Utopia Video Studios’ first project was a version of Gustav Holst’s The Planets, a demonstration disc for Videodisc by RCA SelectaVision. It was a harbinger.

Throughout the next decade, Rundgren began to devote more time to technological developments than his own music. Nevertheless, the early ’80s were a robust time for Rundgren – his last great period of commercial success. He came back swinging in 1980, releasing two albums with Utopia: the shiny pop/rock opus Adventures in Utopia and the cutting Beatles parody Deface the Music. He also released “Time Heals,” the first music video to combine computer graphics and live action; it would later be the second video played on MTV. The following year, he released his first solo album in three years, the spiritually inclined Healing. By this point, his relationship with Bearsville Records had become increasingly rocky. Utopia delivered one last album for the label, 1982’s Swing to the Right, before departing for the fledgling Network label, releasing Utopia that same year. After completing a groundbreaking solo tour in 1982, which alternated acoustic sets with sets featuring taped backings and video backdrops, he released The Ever Popular Tortured Artist Effect. Despite the presence of a moderate novelty hit with “Bang the Drum All Day,” the album didn’t eclipse Healing on the charts.

As he attempted to leave Bearsville, Rundgren found himself in further record company difficulties when Network folded. Utopia then moved to Passport, yet another new record label. In 1983, after he devoted some time off to do technological work, he reconvened Utopia, who released Oblivion in 1984. Oblivion did respectably on the charts, peaking at 74, but the next year’s follow-up, POV, tanked – it reached only 161. Part of the problem was Utopia’s sound had indeed changed, but it was no longer contemporary. Following POV, Rundgren effectively pulled the plug on the group, although he would later reunite the band for an occasional tour. Rundgren’s next solo album, A Cappella, featured nothing but his voice, albeit multi-tracked and sometimes processed beyond recognition. Negotiations with Bearsville held up the release of A Cappella for months. Once the deals were completed, Rundgren was finally free of Bearsville and he signed to its new parent company, Warner, who released A Cappella in September 1985. It did fairly well on the charts, but it was treated more as a novelty than a full-fledged record by both critics and fans.

Rundgren spent the next few years working on computers, as well producing. In 1986, he was hired to produce the cult British pop band XTC. Over the course of the recording sessions, tensions grew between Rundgren and the group’s main songwriter, Andy Partridge, eventually spilling over into outright hostility. Nevertheless, the resulting album, Skylarking, revitalized XTC’s career and Rundgren’s producing career. Although he had a few high-profile gigs afterward – such as with Bourgeois Tagg and the Psychedelic Furs – he decided to continue with his own technological and musical endeavors. In 1989, he finally released Nearly Human, his soul-spiked follow-up to 1985’s A Cappella. Staying on the charts for 11 weeks, it was Rundgren’s last album to come close to a mainstream hit, thanks to the radio single “The Want of a Nail.” Several songs on Nearly Human were also used in his musical score for the off-Broadway production of Joe Orton’s Up Against It, which was originally the script for the unfilmed third Beatles movie.

A collection of new material recorded live, 2nd Wind, appeared in 1991. It was Rundgren’s final record for Warner and the last record he would make for a major label. The following year, he reunited Utopia for a tour of Japan, then he set to work on his first album for Rhino’s new music division, Forward. Released under the moniker TR-I – from this point on, he used TR-I to distinguish his technologically innovative work – No World Order was an ambitious project. Not only was it released as a conventional CD, it was also released as an interactive CD-ROM through Philips and Electronic Arts. It certainly earned him press, but the reviews didn’t lead to sales. Frustrated, he left Rhino, releasing The Individualist on ION in November 1995. Like its predecessor, the album was designed as a groundbreaking technological innovation – this time, however, it was an enhanced CD. The Individualist earned better reviews than No World Order, particularly among computer-based publications.

During this time, he also worked as a DJ on the acclaimed syndicated radio program “The Difference with Todd Rundgren.” The show was nominated for several awards, but its production was ceased in November 1996 due to an altered show format. He also did several television and film soundtracks, including the hit Farrelly Brothers movie Dumb and Dumber. In 1997, the fledgling Angel Records off-shoot Guardian Records offered Rundgren a significant amount of money to re-record many of his hits and cult favorites as a bossa nova record. Clearly, Guardian was attempting to capitalize on the lounge fad of the mid-’90s, but Rundgren took the bait, supporting the resulting record, With a Twist, with a full-fledged tour. Prior to hitting the road in the U.S., he was one of the first Western artists to perform for the Chinese during the summer Shanghai Festival. That year saw the first release of his Up Against It songs through the Japanese label Pony Canyon.

He also inked a deal to host a weekly online radio program, called “Music Nexus” for the EnterMedia Network. In fact, the Internet became the main focus of Rundgren’s career by the end of the ’90s. In 1996, Rundgren launched Waking Dreams, a collective that developed creative ideas in marketable commodities. Perhaps more importantly to the music industry, Rundgren also founded PatroNet, an innovative device that lets users subscribe to music offered directly from his site – with no record company middlemen at all.

During all this, Rundgren continued to work on new music – intending to distribute his new material a song at a time through PatroNet – as well as write his much-delayed autobiography (despite short previews on his official website, it’s yet to be published). The late ’90s saw Rundgren return to the road for several different tours – both as a solo performer and as part of Ringo Starr’s All-Starr Band, as he also continued to produce other acts (Splender’s Halfway Down the Sky, Bad Religion’s The New America, etc.). The emergence of numerous archival projects began to surface in the early 21st century, such as The King Biscuit Flower Hour Presents and a slew of Japanese-only rarity sets as part of the ongoing Todd Archive Series (as of mid-2001, 11 different sets had been issued – comprised of outtakes, demos, and full concerts over the years featuring Rundgren solo, Utopia, and even the Nazz), as well as a compilation of tracks that has only been available previously on his PatroNet service, titled One Long Year.

In the summer of 2001, Rundgren participated in the A Walk Down Abbey Road: A Tribute to the Beatles tour, which also included Ann Wilson (Heart), John Entwistle (The Who), and Alan Parsons (the Alan Parsons Project).

Stephen Thomas Erlewine & Greg Prato, All Music Guide (allmusic.com)