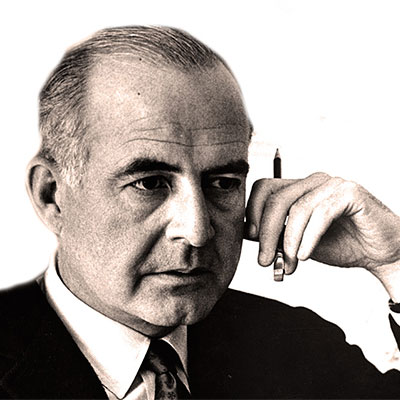

Samuel Barber

Inducted: 1989

An open-hearted yet tough romantic, Samuel Barber was one of the few twentieth century American composers to fight for the primacy of lyricism. In his last decades he seemed to be losing the battle, but by the end of the century Barber had posthumously become one of America’s most widely performed and recorded composers. In particular, his emotive Violin Concerto and Adagio for Strings have gained a popularity exceeded only by certain works of Aaron Copland.

Barber entered the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia in 1924, where he met future opera composer Gian Carlo Menotti; the two would become lifelong lovers. Barber was an able pianist and a baritone of some talent, but he was an even more precocious composer. His 1933 Curtis graduation piece, the spirited School for Scandal Overture, has become a beloved concert opener.

Barber developed into America’s most enduring composer of art songs; most popular is his tender setting for soprano and chamber orchestra of James Agee’s Knoxville: Summer of 1915. Barber had unerring taste in texts, and his literary interests led him to compose some allusive short orchestral pieces. Yet he was particularly adept at writing abstract works, such as Music for a Scene from Shelley. Many of these are in large forms: two symphonies, one string quartet (from which was drawn the Adagio for Strings, first popularized by Arturo Toscanini), an ambitious piano sonata, and one concerto each for violin, cello, and piano. While following traditional formats, they are propelled by a dramatic expressivity that hadn’t been fashionable since Sibelius. Equally direct in their emotional content are his three Essays for Orchestra, the second being the best crafted and most acclaimed.

Barber would have seemed an ideal composer for the stage, but he had limited success in that realm. Medea, a 1947 dance score for Martha Graham, has found greater longevity in orchestral excerpts. His 1958 Vanessa garnered him the first of two Pulitzer Prizes (the second was for his Piano Concerto), but, like most other American operas, it quickly dropped out of sight. Barber wrote Anthony and Cleopatra to open the new Metropolitan Opera House in 1966, but critical reaction was so hostile that he produced very little during his remaining 15 years. Barber was too conservative to be fashionable; his harmony could be astringent, but his tonality remained secure, his rhythms were strong and clear, and he was not above writing a good melody.

James Reel, All Music Guide (allclassical.com)